December 5, 2022

Farmers and traders hoped not to see a repeat of last year’s drought and low yields, and in the most part, this year’s dry pea, lentil, and chickpea crops have delivered. Luke Wilkinson reports.

When trying to understand the 2022 lentil, dry pea, and chickpea crops in the United States, it is important to take into account the significant effects of the drought that plagued the growing regions in 2021. Some pulse classes saw a drop in yield of more than 50% year-on-year.

This year, drought was expected to be less of an issue and there has been a sense that the industry could rebound with less abandonment, higher yields and renewed confidence. This report aims to lay out the performance and final numbers of three different classes: lentils, dried peas, and chickpeas, exploring the ups and downs of the growing season and its resulting harvest.

We will be chatting with industry professionals, and taking into account the NASS test production reports, as well as using data collected from industry sources in order to give you the most up-to-date information and market analyses possible.

"We had a huge drought throughout all the growing areas last year," says Jeff van Pevenage, CEO of Columbia Grain International, “so while we've had good carryover stocks over the years, going into this year carryover on almost all pulses was getting very very tight."

The production numbers for 2021/2022 explain the cause of the tight numbers: dry green peas took a 38% drop in yield, lentils a 21% drop, and chickpeas a 52% drop overall. Total production for green and yellow peas went down nearly 100%, lentils were down by 57%, and chickpeas also slumped by 29%.

Van Pevenage continued, "As the seeding season began in 2022, Western Montana continued to be in drought. Western North Dakota on the other hand actually had a little too much rain and were having problems getting seeded. Washington and Idaho had had a nice winter with good moisture in the growing area and looked set for ideal weather, but that continued into June.”

There has been some disappointment with Pardina lentils in Washington state, which appears to be the result of some chemical damage caused by the early excess moisture.

“That crop,” says Van Pevenage, “which I thought was going to be the best lentil crop in the US, turned out to be just average or below average.”

“The Montana lentil drop in the western part of the state was no better than the drought year last year, maybe because it was still in drought when things were seeded. Yields in what we call the Golden Triangle of Montana were not very good for lentils and peas. Eastern Montana, where the majority of pulse crops are, actually had a decent crop from lentils, peas, and chickpeas.”

After the drought year of 2021, acreage for dry peas and chickpeas shrunk significantly, while lentil acreage rose slightly, though an improvement in yield in all cases would most likely see a return to the average in terms of production.

Dry pea acreage was approximately 863,000 acres, lentils approximately 633,000 acres, and chickpeas around 350,400 acres. This represented a drop in dry peas and chickpeas of 5% and 4% respectively. Lentil acreage rose by 15%.

This report uses some of the most recently available industry data as supplied by the USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council (USDPLC) and the American Pulses Association (APA) using statistics collected by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Farm Service Agency (FSA), and the Department of Commerce. Using this data set, we can provide an approximation of the production data for dried peas, lentils, and chickpeas.

The production numbers themselves appear to be quite mixed, with some improvements in yield from last year but in other cases, such as dry peas, yield has actually decreased.

We will explore production numbers here in as much detail as possible, taking each class one at a time.

Source: USDBC/APA Report - Pulse Pipeline Nov. 22

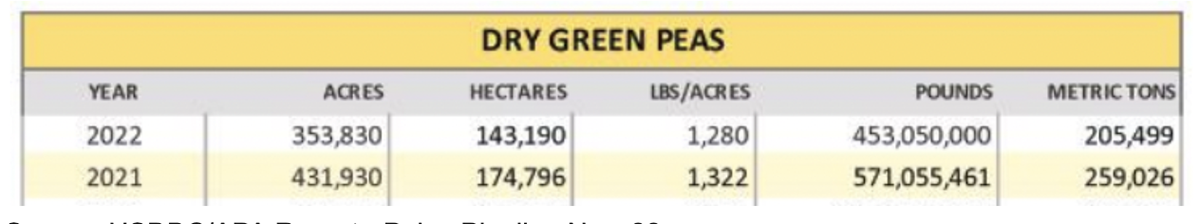

Dry green pea production is estimated at around 205,500 metric tons. In 2021, total production was 259,026 metric tons, which means that total production has dropped by roughly 21% year-on-year. The 2022 total green pea harvest is roughly 45% below the 10 year average.

Yield has also dropped year-on-year and significantly against the 10 year average. This year’s yield is estimated at around 1280 lbs per acre, which is a 3% drop compared to 2021 and a 32% drop against the 10 year average.

Source: USDBC/APA Report - Pulse Pipeline Nov. 22

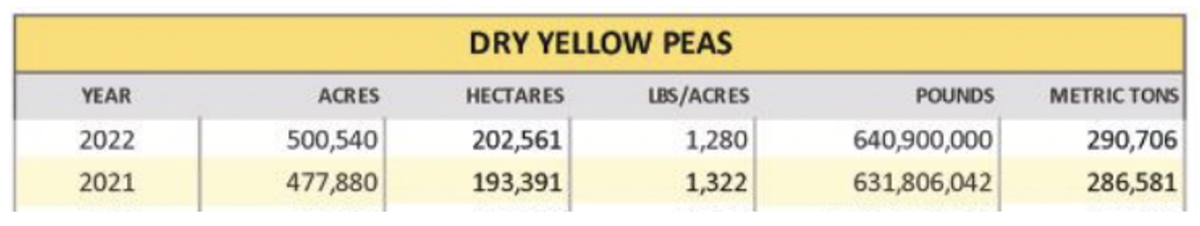

The dry yellow pea production is estimated at around 290,700 metric tons, representing a rise of nearly 1.5% compared to the 2021 crop. It is, however, an approximately 40% drop from the 10 year average of 497,995 metric tons.

Overall yield for yellow peas this year is suggested to be approximately the same as green peas, as such, the drop in yields is thought to be roughly identical.

Source: USDBC/APA Report - Pulse Pipeline Nov. 22

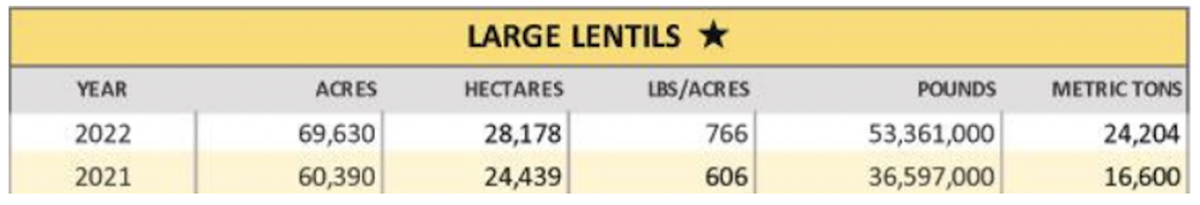

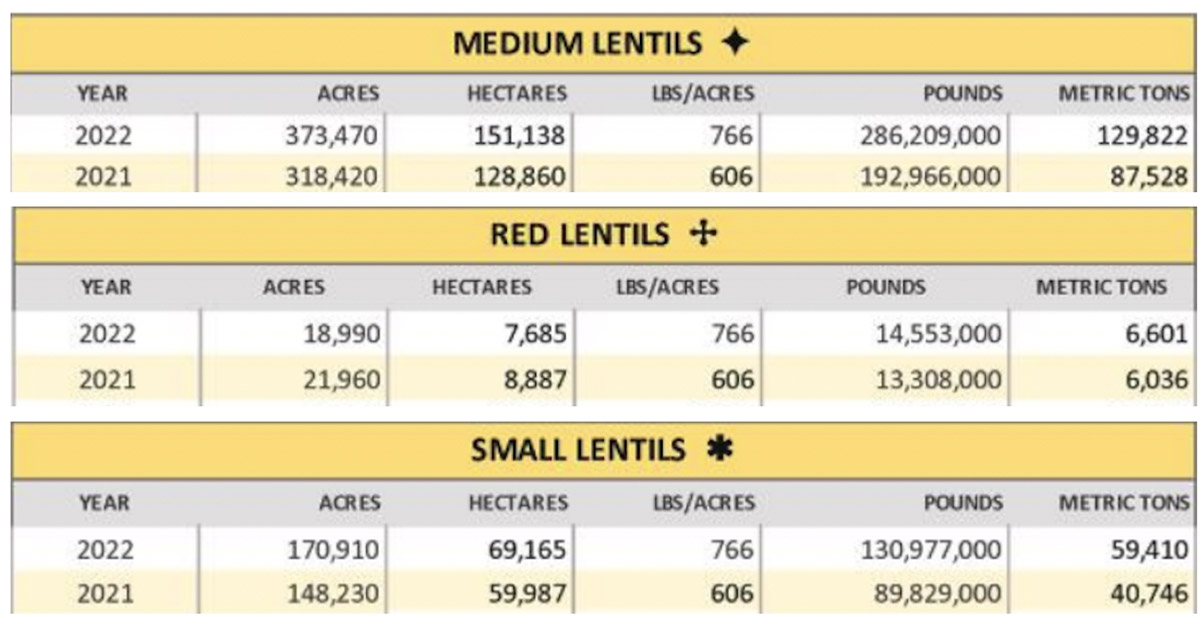

Unlike dry peas, lentils seem to have made small improvements in both yield and overall production. Production appears to be just over 220,000 metric tons, which places the rise in production at 45% compared to 2021's harvest, which came in at 150,910 metric tons. This makes the 2022 production for lentils roughly 5% lower than the 10 year average in the US.

Yield for lentils in 2022 is thought to be higher than last year; at approximately 766 lbs per acre this is our rise of roughly 26% year-on-year, but around 37% less than the 10 year average yield.

Source: USDBC/APA Report - Pulse Pipeline Nov. 22

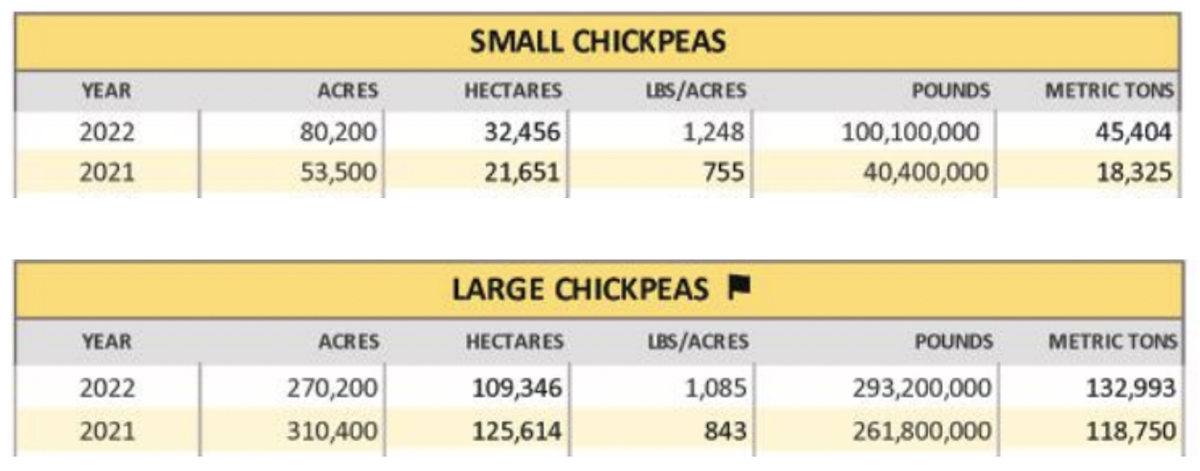

Chickpeas are the most improved of the three pulse classes explored in this report, with production having risen from over 137,000 metric tons to just over 220,000 metric tons - a 60% uptick in total production year-on-year, but 12% drop from the 10 year average.

Yield for chickpeas is much improved from the previous year's drought, coming in at over 1100 lbs per acre compared to 799 lbs per acre in 2021 - 37% rise year-on-year, and a roughly 27% drop against the 10 year average yield.

With production levels for peas and lentils looking distinctly average, we might wonder what implications this will have for the markets.

What kind of carryover can we expect for this year?

Jeff Van Pevenage suggests that carryover will be on the low side, “I think US carryover will be very, very tight. You'll probably find us somewhat uncompetitive in the world and I believe that over the next year you're going to see more food aid for both US food banks and international food aid. We’re also seeing an increase in the petfood and protein businesses within the US, so yellow please are not as much of an export item for the United States anymore. To me, it looks like all of our peas, lentils, and chickpeas will end this marketing year in very tight conditions."

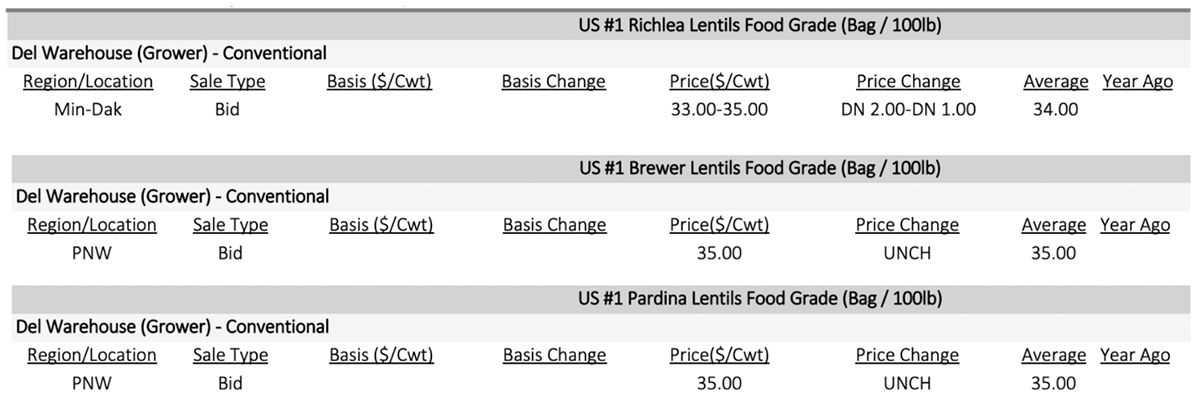

Lentil bid prices as of 29/11 are as follows:

Source: USDA - Weekly Bean, Pea, and Lentil Market Review

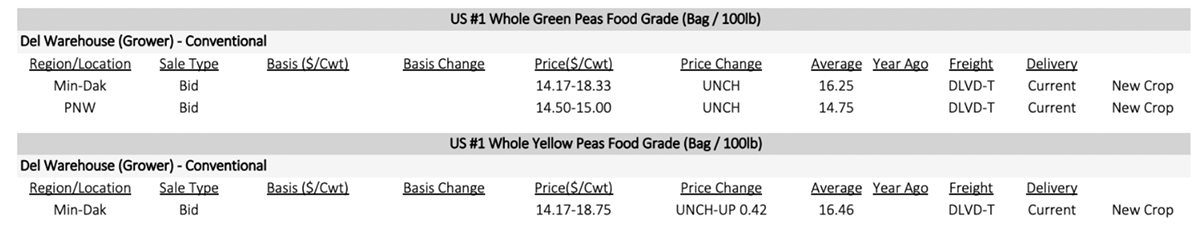

Source: USDA - Weekly Bean, Pea, and Lentil Market Review

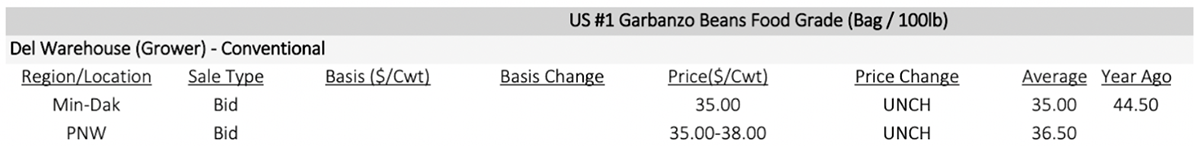

Things look good for this year’s chickpea crop, Max Hinrichs explains: “I think around 25% of the crop will get exported. Pakistan, the Mediterranean – they're probably the two biggest spots. Looking at size, if we take the average size of the Pacific Northwest, we can say that 20% of it might be small, 70% of it would be 9mm, and the balance would be 10 mm. The domestic market wants 6-8 mm - they're looking for inexpensive chickpeas.”

On prices, Hinrichs suggests that the US price will hold: “I see our crop maintaining fairly well going into the Argentinian harvest – it will depend on what they do. I think they’re needing more money to compete in the rest of the world too, so when I look at the price structure for the next year, I think it'll be similar to this year."

Source: USDA - Weekly Bean, Pea, and Lentil Market Review

Asked about the coming years’ pulses acreage, Jeff Van Pevenage responded that acreage may be squeezed by other crops next year, and possibly in the years to come: “One thing you're seeing happened in the US is that farmers are having problems with what's called Italian rye and now they need to add more canola or oilseed to their rotations. So you're seeing more oilseed acreage move into Montana, into Washington, and Idaho. That most likely comes at the expense of pulse crops."

Commodity crop prices are high, and canola is amongst those likely to compete with pulse acreage but will the shift into canola crops be permanent?

“I don't know about permanent," says Van Pevenage, "but let's just say that the next 10 years looks like more canola acreage in rotations - some of that is driven by the weather, but more of that is probably driven by what is good and sustainable for the land.”

Van Pevenage estimates that roughly 10 to 15% of what would normally have been pulse acreage became canola acreage this year.

USA / Jeff van Pevenage / Columbia Grain International / green peas / lentils / chickpeas / yellow peas / USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.